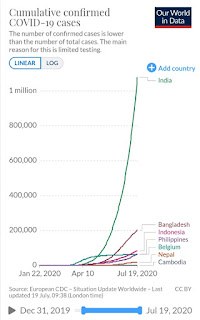

The COVID-19 pandemic has passed 13 million, killing over 570.000 people worldwide. Every day, the number of new cases set another daily record. Many health experts say the actual number of cases around the world may be much more than the reported numbers. Vaccines can take at least a year to develop before they are proved to be safe and effective. The pandemic is taking a huge toll on health, economy and social life around the world.

Epidemiological characteristic of COVID-19 showed that virus infections tend to be more severe for older peoples and those with pre-existing health conditions, which unfortunately occur more frequently in disadvantaged groups, groups of people who have less or no access to health care, or more likely to live and work in conditions that increase the risk of infection. The policies to contain it could even widen pre-existing inequalities.

Countries have adopted various forms of policies and measures to “flatten the curve”, including a range of public health and social measures, movement restrictions, closure of schools and businesses, restriction on social-religious-sports-entertainment activities, quarantine in specific geographic areas and international travel restrictions. With school closures in over 190 countries, children’s education -especially for the girls- is at risk and potentially increases child labour. As education and training have been disrupted, young people have greater obstacles for their transition from school to work, their start-up business have seen collapses, and a current wave of job losses have hampered employment opportunities and earning, forcing more than one in six people aged under 29 to stop working. Anxiety or depression among young generation led many to dub them the ‘lock down generation’.

Many countries are not prepared to handle a pandemic on the scale of COVID-19. The pandemic had a devastating effect on health systems in countries like Bangladesh and Nepal. India’s low investment in the health sector created a severe shortage of healthcare workers. India has a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1/11,404 (Feb 2020), compared to the WHO recommended doctor-to-patient ratio of 1/1.000. The opening of the largest emergency hospital in the world in Chattarpur, New Delhi with 10.000 beds could not catch-up with the existing 0,53 beds per 1.000 people’s ratio. The lock down measures were only able to borrow time but in such a dire situation, the worst is yet to come.

Healthcare workers and social workers are at the frontline of this tragedy. According to the International Council of Nurses, more than 450.000 health care workers have been infected by COVID-19 and 600 nurses worldwide died. In the Philippines, 3.122 health workers have been infected, 33 have died. Li Wenliang, a Chinese doctor from Wuhan who tried to warn about the outbreak and died of COVID-19, and many more medical heroes shall be honoured and remembered. Doctors, dentists, nurses, physicians, ambulance drivers, cleaning staffs and other health workers have become some of the most dangerous jobs in the world.

With border closures, migrant workers can’t return to their country of origin, trapping them in destination country without jobs, income or food. Many workers were forced to quarantine in squalid crowded labour camps, many without access to health services, causing a surge of COVID-19 infections among migrants. In Singapore, over 93% of the total cases were migrants with over 93% of the total cases related to dormitories. Worst, migrant workers are discriminated and often seen as the primary causes for a wave of infections.

According to the ILO, the COVID-19 crisis is affecting the world’s workforce of 3.3 billion. Extreme reductions in economic activities are causing a dramatic decline in employment, both in terms of numbers of jobs and aggregate hours of work. Tourism has been among the worst affected of all major economic sectors. Compared to other sectors, tourism sector will most likely take a long time to recover as people behaviours changed to become more cautious about travelling. Countries like Nepal and Indonesia have experienced a 99% drop in number of tourists. As half the planes worldwide remain grounded, the number of passengers taking flights has fallen drastically, a 95% drop compared to 2019.

According to the ILO, the COVID-19 crisis is affecting the world’s workforce of 3.3 billion. Extreme reductions in economic activities are causing a dramatic decline in employment, both in terms of numbers of jobs and aggregate hours of work. Tourism has been among the worst affected of all major economic sectors. Compared to other sectors, tourism sector will most likely take a long time to recover as people behaviours changed to become more cautious about travelling. Countries like Nepal and Indonesia have experienced a 99% drop in number of tourists. As half the planes worldwide remain grounded, the number of passengers taking flights has fallen drastically, a 95% drop compared to 2019.

The labour-intensive industry in a global supply chain, such as in the garment and textile sector, are hardly hit by the crisis, factories close and workers are told to stay at home, many are losing their jobs. For a garment-textile dependent country such as Cambodia, the crisis put around 1,7 million of jobs at risk and poverty rose to 11%. As demands diminished, factories have tons of cancelled orders which caused massive lay-offs or salary reductions, dropping these already low-income workers back into poverty.

|

| © Kandukuru Nagarjun |

Women, overrepresented in the informal sector—70% globally, bear the brunt of the crisis in many dimensions. Prolonged stays at home increase the burden of care work, as well as make it harder to escape domestic violence.

The pandemic has been a great challenge for the health and social protection system around the world. It has exposed serious gaps in access to health care and social protection systems around the world, particularly for workers in the informal economy, non-standard forms of employment and migrant workers. Globally, as many as four billion people (55% of world’s population) are not covered by social protection. The crisis has forced governments to take policy responses by extending social protection systems through broad ranges of measures, from extended sickness benefits to unemployment protection schemes and unemployment benefits to laid-off workers.

According to ILO Monitoring on Social Protection, 108 countries announced at least 548 social protection measures to lessen the devastating impact of lost jobs and livelihoods due to pandemic. Around 19% are related to special social allowances/ grants, closely followed by measures relating to unemployment protection (15%), health (10%) and the allocation of food (9%). According to the Labour department of Indonesia, the government took five measures to respond: tax incentives for 56 million formal workers, pre-employment scheme for 8,4 million laid-off workers, extending protection for migrant workers, public works for creating jobs, social scheme for 76,5 million workers in informal economy and stimulus for companies who did not fire their workers.

Lots of initiatives have been taken by ANRSP members in the countries to assist workers and populations during lock down due to the pandemic. These range from providing direct health assistance, COVID-19 rapid test, developing testing kits, distribution of food and basic needs, transporting workers, legal assistance for laid off workers, access to social security, negotiating benefits for workers, financial assistance, media campaign on public health information, and social dialogue with the government, employers and social security agency on social policies to response the pandemic and its impact on employment.

THE NEW NORMAL

There are too many unknowns right now for scientists to say when the pandemic will be over due to the mutation rate of the virus and how human antibody respond to it. In the absence of better knowledge about the virus, some countries started to lift lockdown restrictions to allow economic activities to continue with health protocols in places. Gradually, certain businesses opened up, factories began production, restaurants and markets opened, public transports and aviation started running, and other public spaces are open, sometimes at half capacity.

This relaxation of lock downs and restrictions doesn’t mean we should return to a normal situation, the same as before the pandemic. On the contrary, new clusters of cases are seeing record daily case numbers as economic and social life return. The reproduction number or rate of infection in India, for example, is still between 1,11 to 1,69. The WHO warned that the coronavirus "may never go away" even if a vaccine is found. The virus may become just another endemic virus, in part because COVID-19 can be transmitted by people who are infected but aren't showing any symptoms. By the time people know they're sick, they may have already spread it to others. Therefore, COVID-19 becomes everybody's concerns, and we should all contribute to making outbreaks more manageable. This is going to be the New Normal.

Under WHO’s coordination, a group of experts with diverse backgrounds is working towards the development of vaccines against COVID-19. Global leaders unite to ensure everyone can access new vaccines, test and treatments for COVID-19. Around 7,6 million people or about half of infected peoples have been cured, raising hope that we have a chance to contain the virus.

ILO has released a policy Framework in response to COVID-19. There are four key pillars in tackling the COVID-19 crisis based on the International Labour Standards:

- Pillar 1: Stimulating the economy and employment

- Pillar 2: Supporting enterprises, jobs and incomes (extend social protection for all)

- Pillar 3: Protecting workers in the workplaces (OSH measures, work arrangements, prevent discrimination and exclusion, provide health access for all and expand access to paid leave)

- Pillar 4: Relying on social dialogue and collective bargaining

NEW SOCIAL CONTRACT: UNIVERSAL HEALTH CARE AND SOCIAL PROTECTION FOR ALL

As we start to enter a ‘New Normal’, we need to craft a ‘New Social Contract’ through social dialogue to transform society and make it more resilient, equitable, sustainable and just. This is the time for policymakers to step-up and address what matters most for all people: leaving no one behind. Swift and coordinated gender-responsive policy responses are needed at national and global level focusing on two goals: universal health coverage and social protection for all, including income protection, as the basis for the Sustainable Development Goals.

Health is a human right and all countries need to prioritize efficient, cost-effective primary health care as the path to achieving universal health coverage. A new approach to health care system should be developed for disadvantaged groups of people, such as elderly or people with pre-existing health conditions. Access to health and health services should be guaranteed especially for those in the rural and remote areas. Community-based health care has always been an essential part of primary care. Health workers are an essential part of health services; therefore, their jobs must be decent. They should receive living wages, including hazard pay, special risk allowances or other benefits.

Governments must ensure that people can access corona virus testing and treatment free of charge. Free and mandatory mass testing must be conducted for all health workers and social workers who are working on the front lines. If a worker is sick or develops symptoms consistent with COVID-19, they should not have to come to work. They should be urged to stay at home, self-isolate, and contact a medical professional or the local COVID-19 information line for advice on testing and referral. Special efforts should be taken to prevent social stigma of workers suspected of being infected, infected with, or recovered from COVID-19, especially in the case of migrant workers.

Health measures to prevent transmission of COVID-19 should apply to all workplaces and all people at the workplace, following the WHO guidelines on adjusting public health measures to different contexts. Protecting workers and their families from infection needs to be a top priority of management and workers alike. Basic health measures include: hand hygiene (hand washing with soap), respiratory hygiene (promoting respiratory etiquette and wearing a mask), physical distancing (at least 1 metre between people and avoiding direct physical contact with others), queue management (through markings on the floor), reducing density of people (no more than 1 person per every 10 square metres), minimizing the need for physical meetings, implementing or enhancing shift or split-team arrangements, reducing and managing work-related travels (cancel or postpone non-essential travel, ensure safe public transport system), regular environmental cleaning and disinfecting, risk communication, training and education, as well as monitoring compliance with these measures.

In labour intensive industries such as garment and textile sectors, companies should have policies to reduce the risk of transmission between workers such as staggered activities, minimizing face-to-face and skin-to-skin contacts, placing workers to work side-by-side or facing away from each other rather than face-to-face, assign staff to the same shift teams to limit social interaction, installing plexiglass barriers at all points of regular interaction and cleaning them regularly. Some workers may be at higher risk because of age or pre-existing medical conditions, which should be considered in the risk assessment of occupational safety and health at workplaces to be carried out in bipartite and tripartite manners, between employers and unions. COVID-19 and other diseases, if contracted through occupational exposure, should be considered occupational diseases.

There can’t be any discrimination regarding access to protective and preventive measures for workers, including for those working in informal economy, domestic workers, migrant workers, outsourced workers and other precarious groups of workers. There should be training of workers in infection prevention and control practices and use of personal protective equipment (PPE). They should have equal access to personal protective equipment as well as to COVID-19 prevention, treatment and care, referral, rehabilitation, social protection, and occupational health services, including mental health and psycho-social support. Medical and care staff need to be adequately protected and equipped.

We urge that income replacement and sickness benefits should be sufficient and extended to all, considering the scope and level of benefits to include prevention measures and the waiting periods for the payment of benefits. Efforts are needed to cover workers not yet covered, such as those in informal economy, non-standard forms of employment and migrant workers. Responsive sickness benefits will indirectly support public health, poverty alleviation and promotion of social security.

Social Protection must be extended to all peoples to close the existing gaps, especially those in the informal economy. Portable access to health services and social security should be provided for migrant workers. Protecting workers in the informal economy through a combination of non-contributory and contributory schemes and facilitating their transition to the formal economy. Some social protection measures should be prioritized and scaled up, covering measures of prevention, protection and promotion. Income support and employment protection have to accompany a safe return to workplaces.

Expanding internet access to cover peoples as much as possible so that it will help ensure access to public health information and combating fake news. Internet access can also support a quality education through distance learning for children currently out of school due to the pandemic. It also can help self-employed people, small and micro enterprises to maintain their businesses. The government should plan how to create a decent and productive employment in the post-COVID-19 economy for young people.

Once a vaccine is available, global leaders must work together to address the impacts of the pandemic to the health of people by ensuring that vaccines are available to everyone without any conditions. Resources can be mobilized at the global and national level on the basis of solidarity and that the strongest shoulders should carry the heaviest burdens in order to ensure sustainable financing of health and social protection systems. Underdeveloped countries should be offered debt relief and urgent international support so they can adopt emergency measures to step up the capacities of their health and social protection systems – including ensuring access to health care and income support. Governments must create fiscal space for universal health care and shock-responsive social protection system. Economy stimuli must focus on lifting poor people, mostly from the informal economy, out of poverty. Coordinated responses to the COVID-19 crisis, can turn things around by building systems that strengthen resilience and enable all people to live in dignity. During its 36th Summit in April 2020 in Vietnam, the ASEAN leaders have set coordination mechanisms to respond to the pandemic by reactivating public health emergency mechanisms, mitigating social and economic impacts of the crisis and increasing resilience of member countries. This is in part due to the ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Social protection and its framework, which helped member countries to better prepare for the crisis.

Finally, the WHO warns that the pandemic 'is not even close to being over'. We are now entering a new and dangerous phase of the pandemic with people tired of lock downs despite the disease’s accelerating speed. Most likely, this virus originated because of the spilling over from bats to pangolins to humans. With human indoors, animals are venturing into the human and urban spaces, the smog-layers skies are clearing, and birds’ songs can be heard once again in cities. Our misplaced appetite for exotic food from the last wild lands has taught us a lot about the relation between human and environment. As we enter the Anthropocene epoch, this is a alarm bell to stop further damage to the climate and mother earth.

The UN agencies which composes of multilateral development agencies, donor governments, and civil society observers (UN Social Protection Inter-Agency Cooperation Board or UN SPIAC-B), have called for urgent social protection measures to respond to the pandemic. The Future of Work Centenary initiative has called for a ‘New Social Contract’, encompassing economic and social policies. The pandemic crisis has demonstrated that all categories of society require universal health care, social protection for all and income protection. Let us seize this standstill to launch into concrete actions.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.