Labour law reform

In 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the central government pushed through with the biggest labour law reform since independence in 1947, to amalgamate and codify 44 existing labour laws into 4 codes in order to simplify the labour legislation in India: a code on wages; a code on industrial relations; a code on occupational safety, health and working conditions; a code on social security. While the central government and some state governments maintain that the labour law reform is necessary in order to boost productivity and to provide greater flexibility to employers to conduct their business, while expanding the social security to both gig workers as inter-state migrant workers. The reform however triggered a serious backlash from trade unions and other labour movements, claiming it as being ‘anti-worker’ and ‘anti-labour’, resulting in a massive general strike held across India on 26th November 2020 in which they claim 250 million workers took part, a majority of them non-unionized and non-organized workers. The main concerns of the broader labour movement are the extension of maximum working time from 8 to 12 hours per day, the introduction of restrictions on the right to strike effectively making industrial actions impossible, and the increase of a threshold for collective layoffs from 100 to 300 workers without prior government approval. The workers’ strike was followed by a march of tens of thousands of farmers to New Delhi to protest against the liberalization of the agricultural sector, which could mean the end of government-controlled wholesale markets and minimum support buying prices for agricultural produce.Coronavirus and lockdown in India

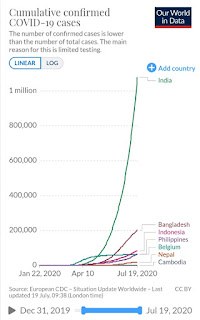

Just like other countries in the world India was struck hard by the COVID-19 virus. On 24th March 2020 a nationwide lockdown was imposed until 14th April and eventually extended until 30th September. This created a lot of chaos as workers, most certainly those in the informal economy (the majority of all Indian workers) could no longer go to work or keep open their business. It led to a collapse in economic activity in the whole country. Due to the loss of income and work, many workers living in the city went back to their family in the countryside, thus contributing to the further spread of the virus. International flights were cancelled and the country’s borders closed, preventing many Indian migrant workers to return home, trapping them for a long time without salary being paid due to the closure of their factory or construction site. Also intrastate travelling became very complicated.

During the first lockdown, partner organizations took the initiative to help the workers and their families in the relief effort, informing them about the nature of the virus and the health risks, distributing personal protective equipment such as masks and hand gels, raising awareness about the importance of quarantine and social distancing, distributing food and medicines.

Although the partner organizations were able to adjust quite fast to the situation, the pandemic and lockdown resulted in the cancelling of many of the originally planned activities. Mainly trainings in groups could not take place or had to be postponed. The partner organizations successfully started to make use of online meetings to stay connected to their members and each other, which became a (less than ideal) alternative for the normal meetings. Most of the partner organizations (except for AREDS) made use of the possibility to reorient 20% of their annual DGD – budget to aforementioned COVID-19 related actions. The partner organizations took this crisis as an opportunity to strengthen the grass root activities by collaborating with different stakeholders and State departments like the police department ( to create awareness), the welfare departments (to give access to welfare/social security schemes to the informal workers), by mobilizing and supporting public distribution of rations and provisions. By involving these different actors and departments, the partner organizations could analyze how government machineries are responding to shocks, how informal workers and grass root level communities were affected by these measures. This helped them to advocate with different trade unions and national platforms and to mobilise for strikes against the Central Government to protest the new labour codes and farmers’ laws.

Aside from the regular DGD – program funds, WSM also channelled funds to the National Domestic Workers Movement from the Music for Life solidarity action and the Brussels Region International (BRI), which has sistered with Chennai, a city in the southeast of India and capital of Tamil Nadu State. BRI supported the NDWM Tamil Nadu branch in supporting domestic workers and their children who have been evicted from the Chennai city center slums and had been relocated 40km away, causing many to lose their jobs and lacking schools. In the second half of 2020, BRI also provided 50.000€ for relief aid to NDWM and 3 other local Chennai organizations. With the support of Belgian organisation Familiehulp, NDWM was also able to start up and develop domestic workers’ cooperatives in six states.